Honpukuji Temple– The Water Temple

Honpukuji Temple– The Water Temple, Awaji, Japan

You arrive at a temple with no roof.

Only water.

A quiet path leads you between concrete walls, the world fading to a hush.

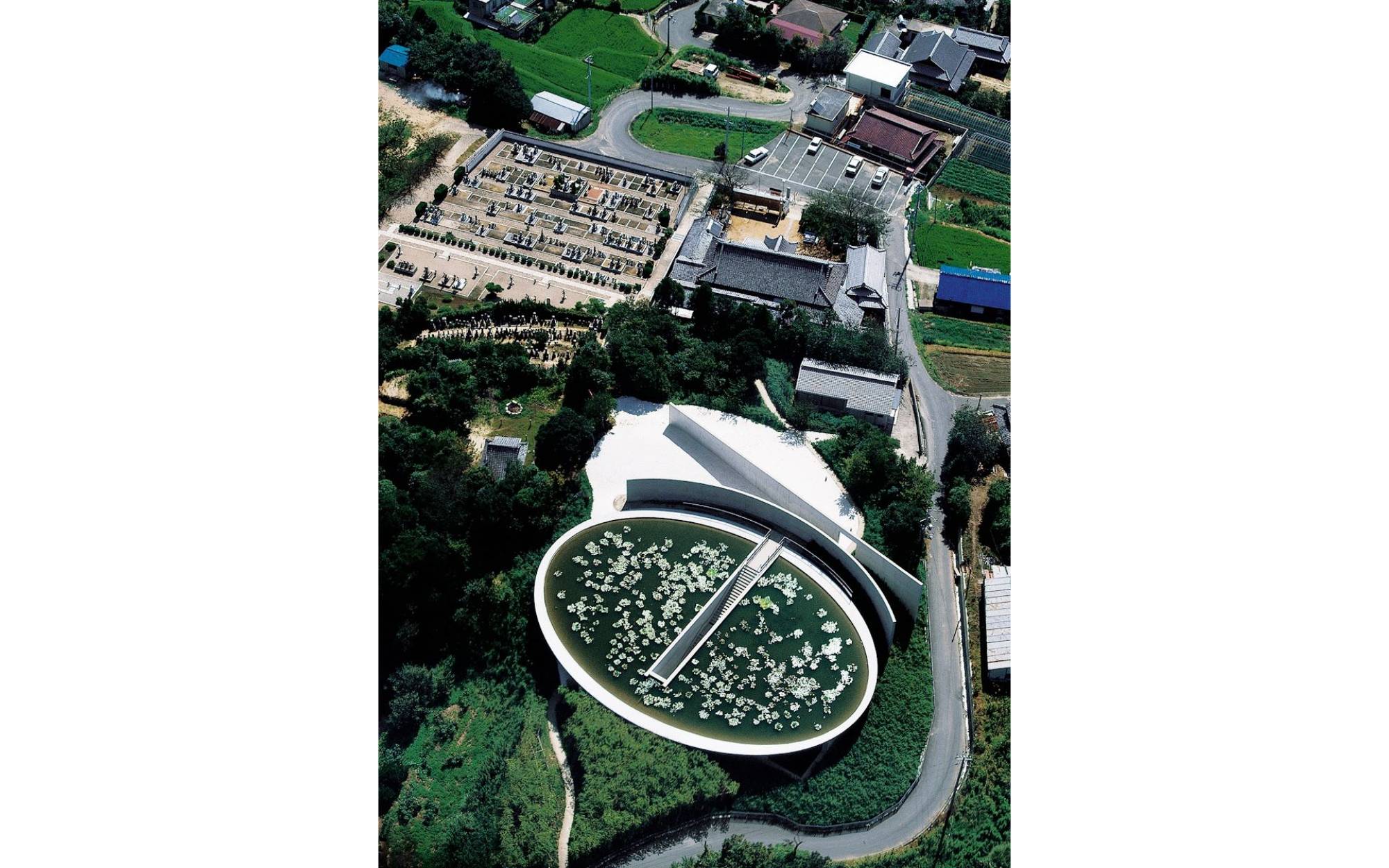

Ahead: an oval lotus pond reflecting sky like a held breath.

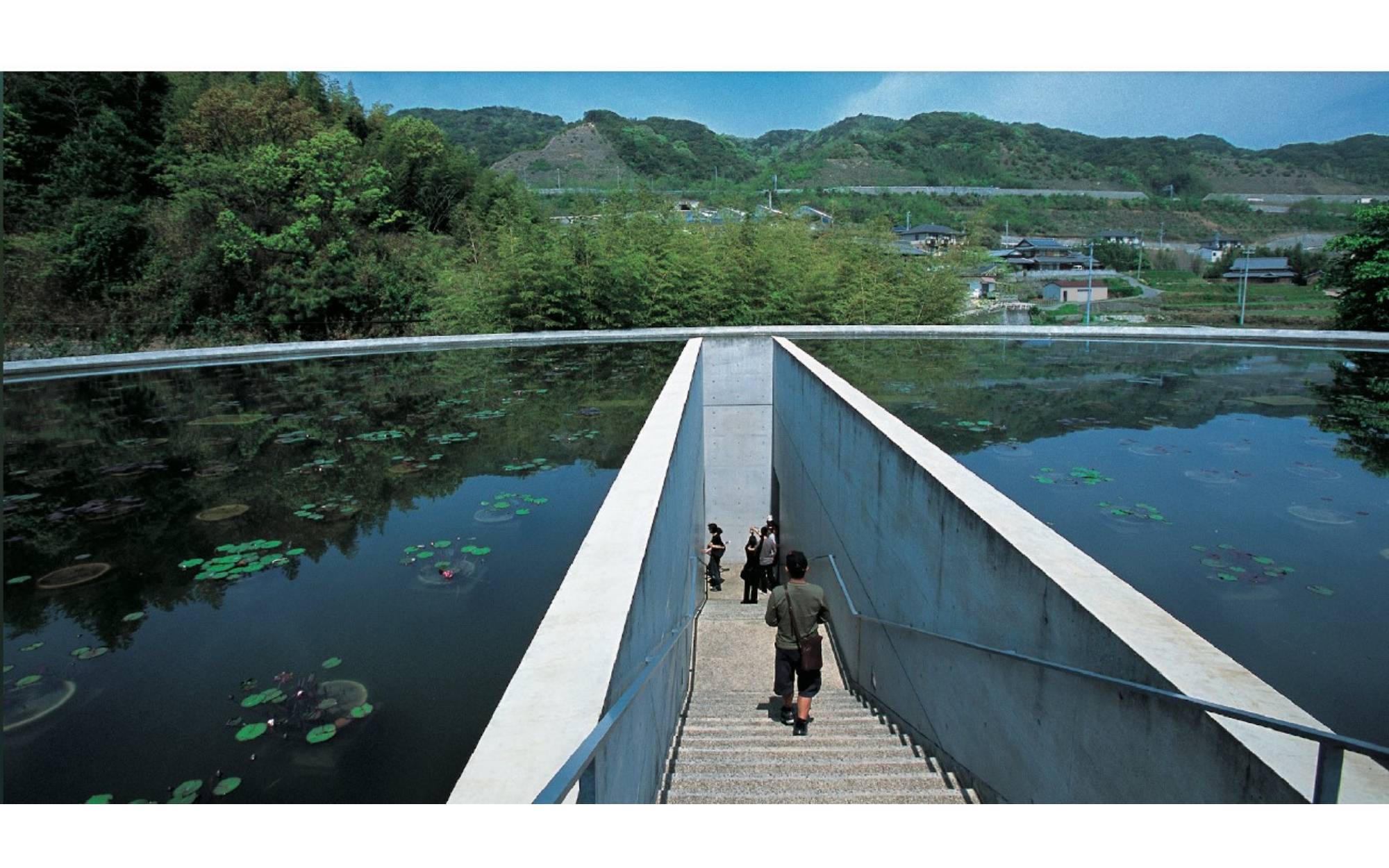

A single cut through the water invites you down.

Step by step, you descend—leaving noise, heat, and hurry on the surface.

Light thins. Air cools. Footsteps slow.

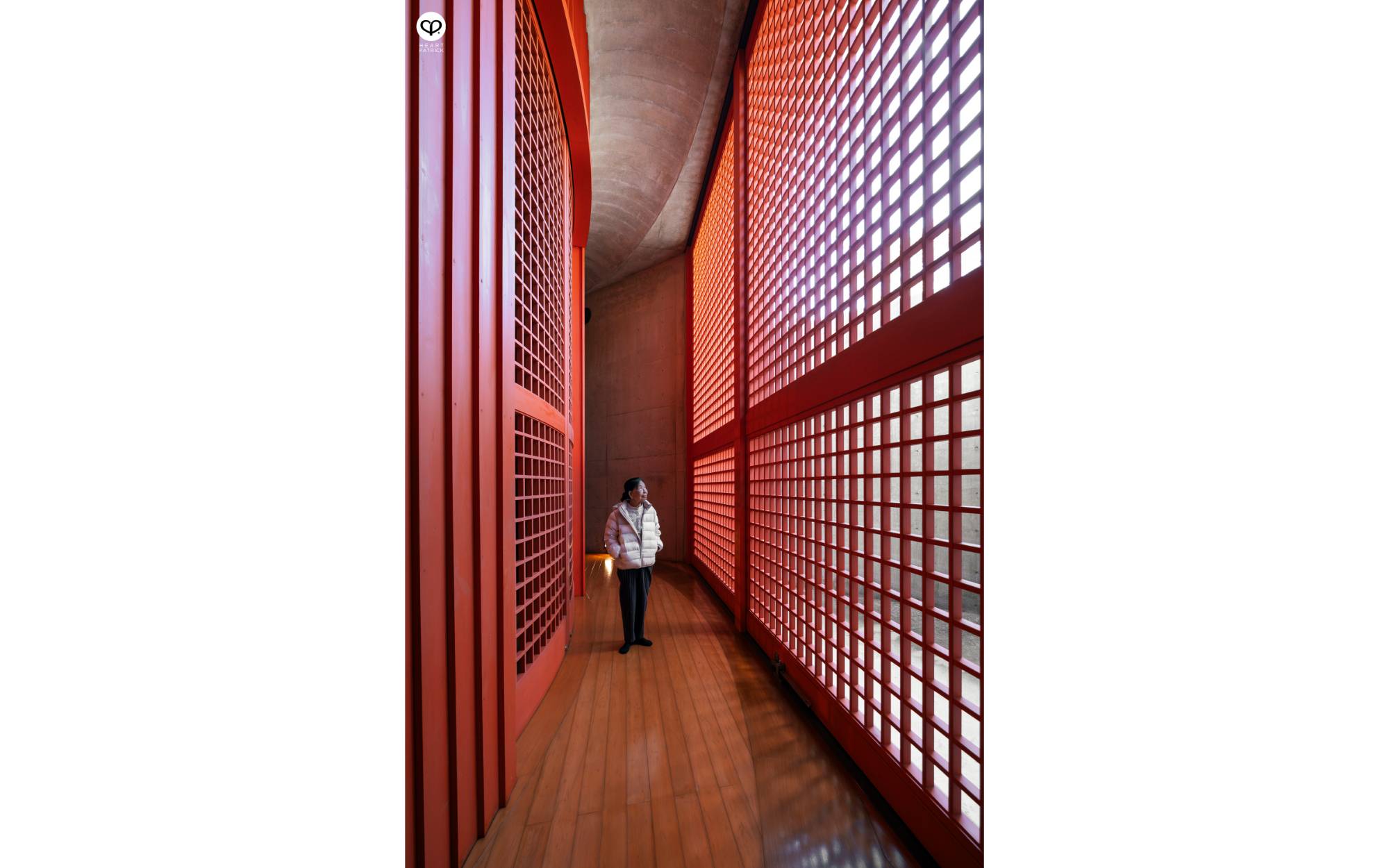

Below the pond, a circle of vermilion glows.

Timber lattice shimmers with soft daylight, as if filtered through the lotus above.

This is Tadao Ando’s Honpukuji—The Water Temple—where the “roof” is a mirror and the threshold is a descent.

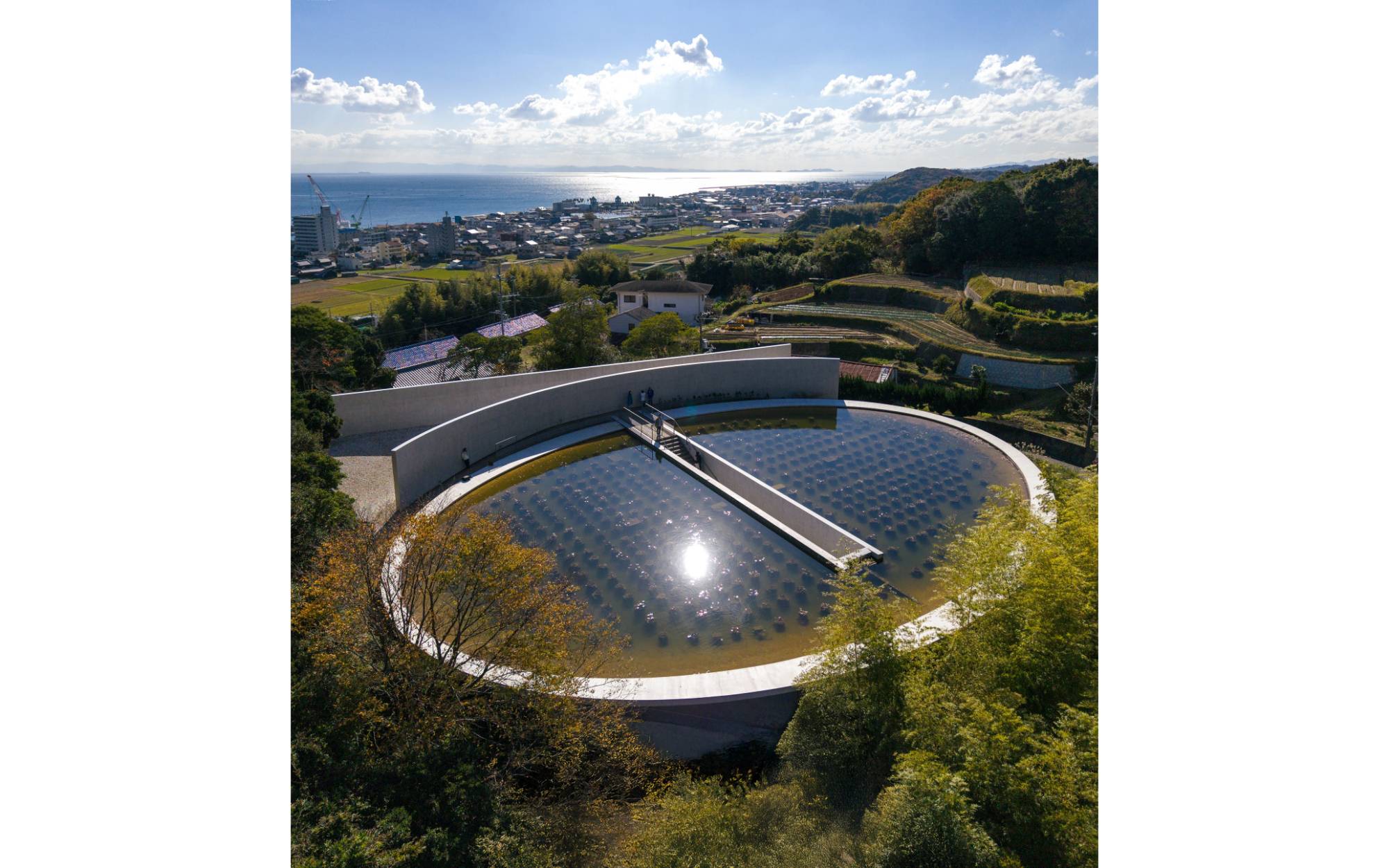

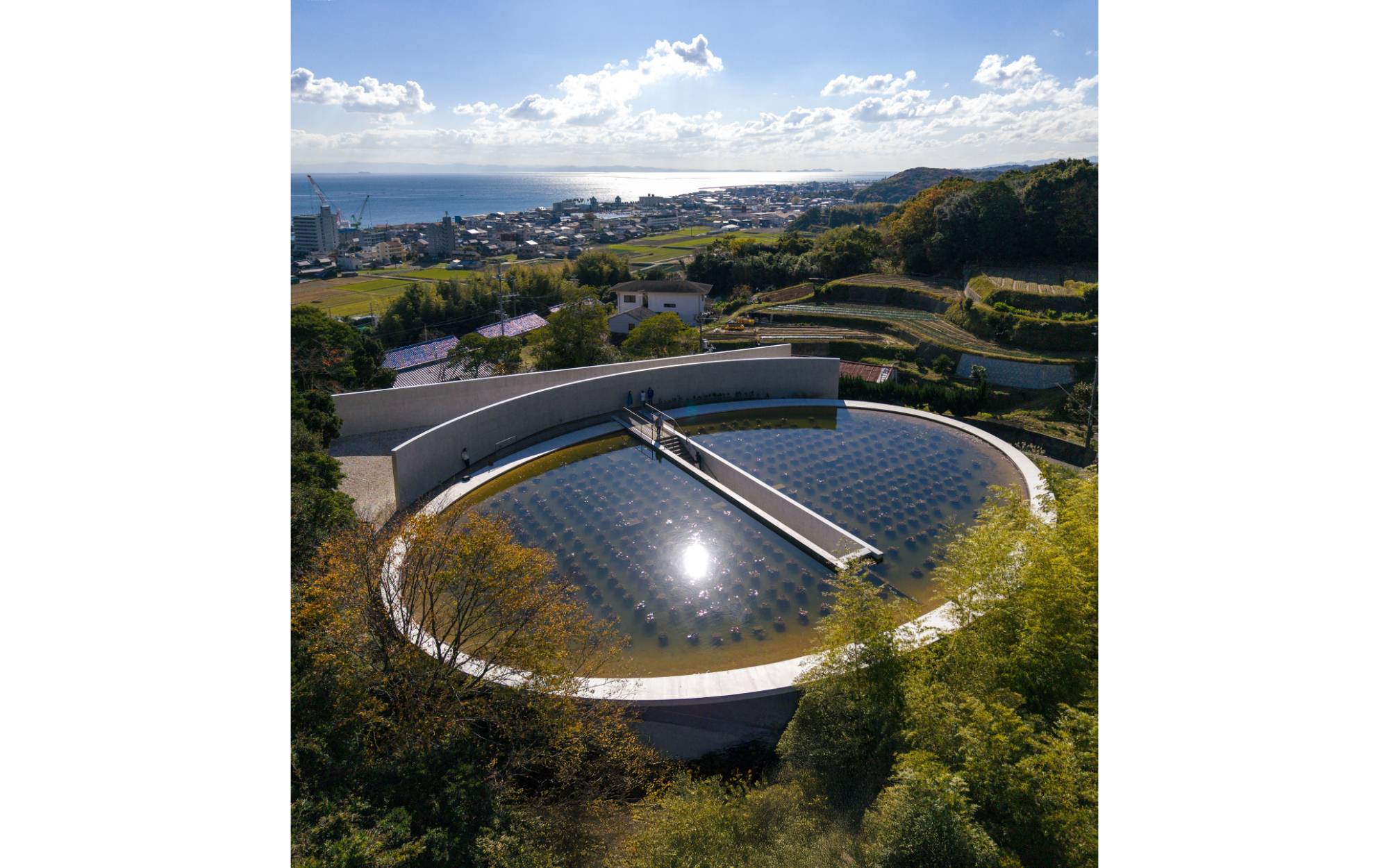

Once upon a time on the island of Awaji, Japan, a quiet hill watched over the inland sea. It was here that Tadao Ando, the poet of concrete and light, chose to build not just a temple — but an experience of meditation through architecture.

As you approach Honpukuji, there are no grand gates or towering pagodas. Instead, you face a serene oval lotus pond, perfectly still, reflecting the sky above. You might think the temple lies beyond it — but no — it lies beneath.

A narrow staircase cuts through the pond, guiding you downward, deeper, into the silence. The further you go, the quieter the world becomes. Concrete walls embrace you, leading to a wooden sanctuary glowing in dim, sacred light.Here, water and faith intertwine. The pond above filters sunlight into gentle ripples below, casting moving shadows over the red interior. Every step is a meditation. Every wall, a pause for breath.

Ando doesn’t ask you to simply look at architecture — he invites you to feel it. To descend into yourself, to find calm beneath the surface noise of the world.

It’s not just a temple.

It’s Tadao Ando’s whisper to the soul:

"Only when you go beneath the surface do you find peace."

History

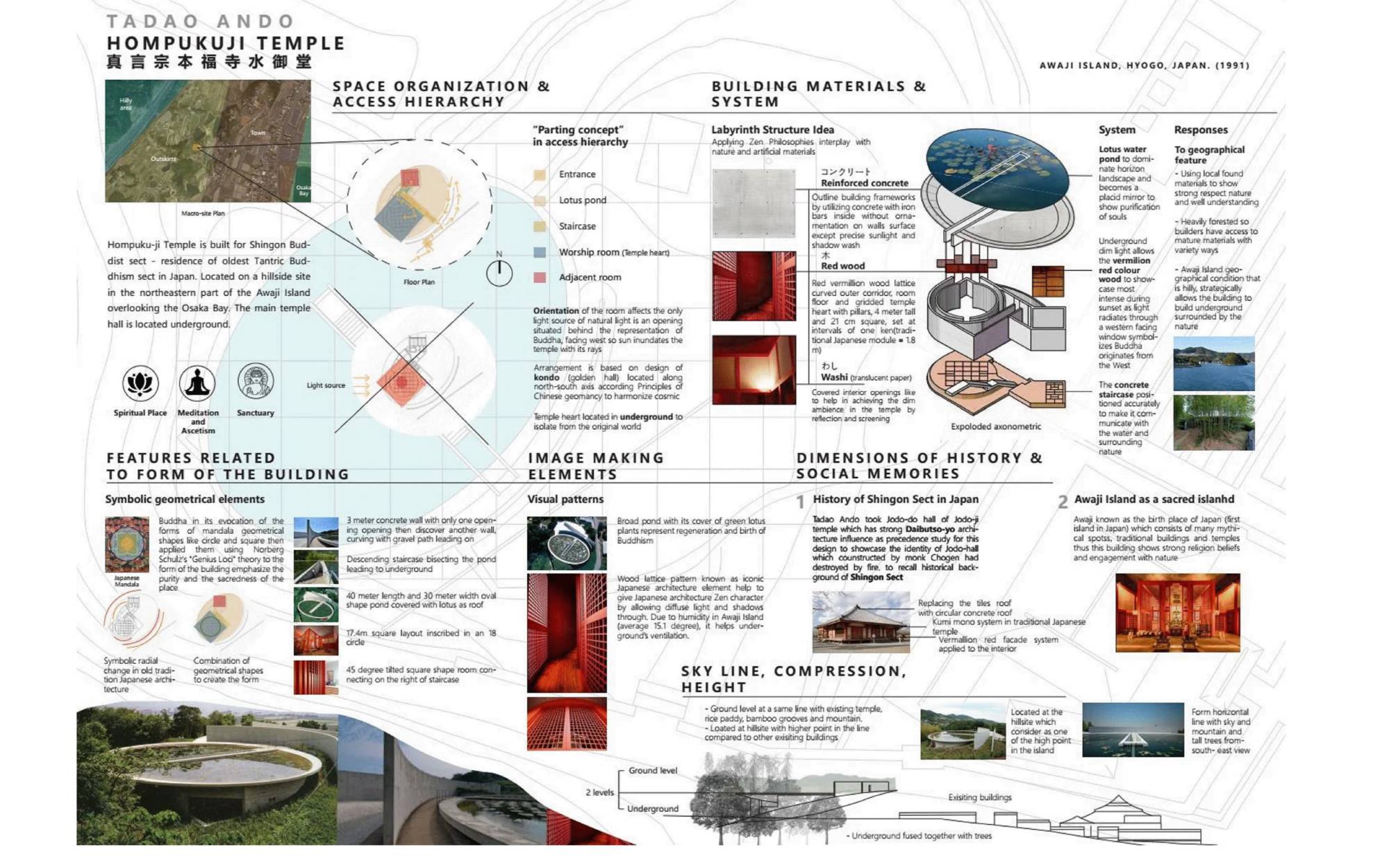

Honpukuji sits on a low hill overlooking Osaka Bay, on Japan’s Awaji Island. The temple belongs to the Omuro school of Shingon Buddhism (head temple: Ninna‑ji in Kyoto). Local records and guide authorities note that a temple stood here since the late Heian period (794–1185), and that Honpukuji serves as No. 59 on the Awaji Shikoku 88‑site pilgrimage. Its principal image is Yakushi Nyorai (Bhaisajyaguru, the Buddha of Healing), designated an Important Cultural Property of Awaji City.

A small country temple, a late‑20th‑century decision

By the late 1980s, Honpukuji’s main hall needed rebuilding. The parish invited Tadao Ando—already renowned for pared‑back concrete architecture—to design a new hall. In 1991, Ando completed what would become one of his most discussed religious works: the Water Temple (Mizumidō), a subterranean worship space set beneath an oval lotus pond.

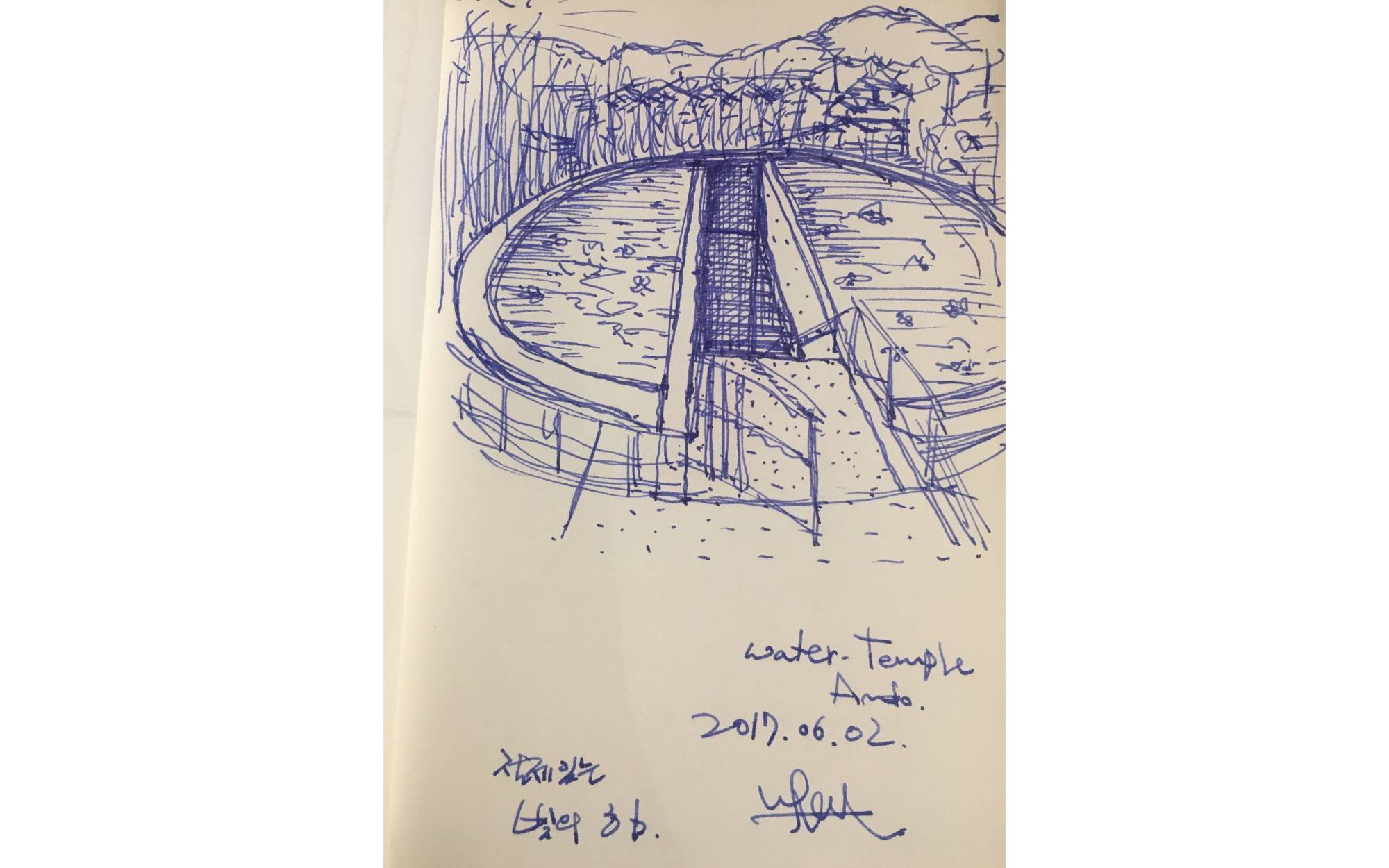

Ando’s idea: replace the roof with water

Approaching his first temple commission, Ando looked to Buddhist symbolism and to images gathered on travels through India and China. Instead of the traditional grand roof, he proposed a flat plane of water planted with lotus, the flower that in Buddhist lore rises pure from muddy depths. The visitor descends a stair that cuts the pond, moving from daylight into a hushed, below‑grade hall.

Procession, space, and light

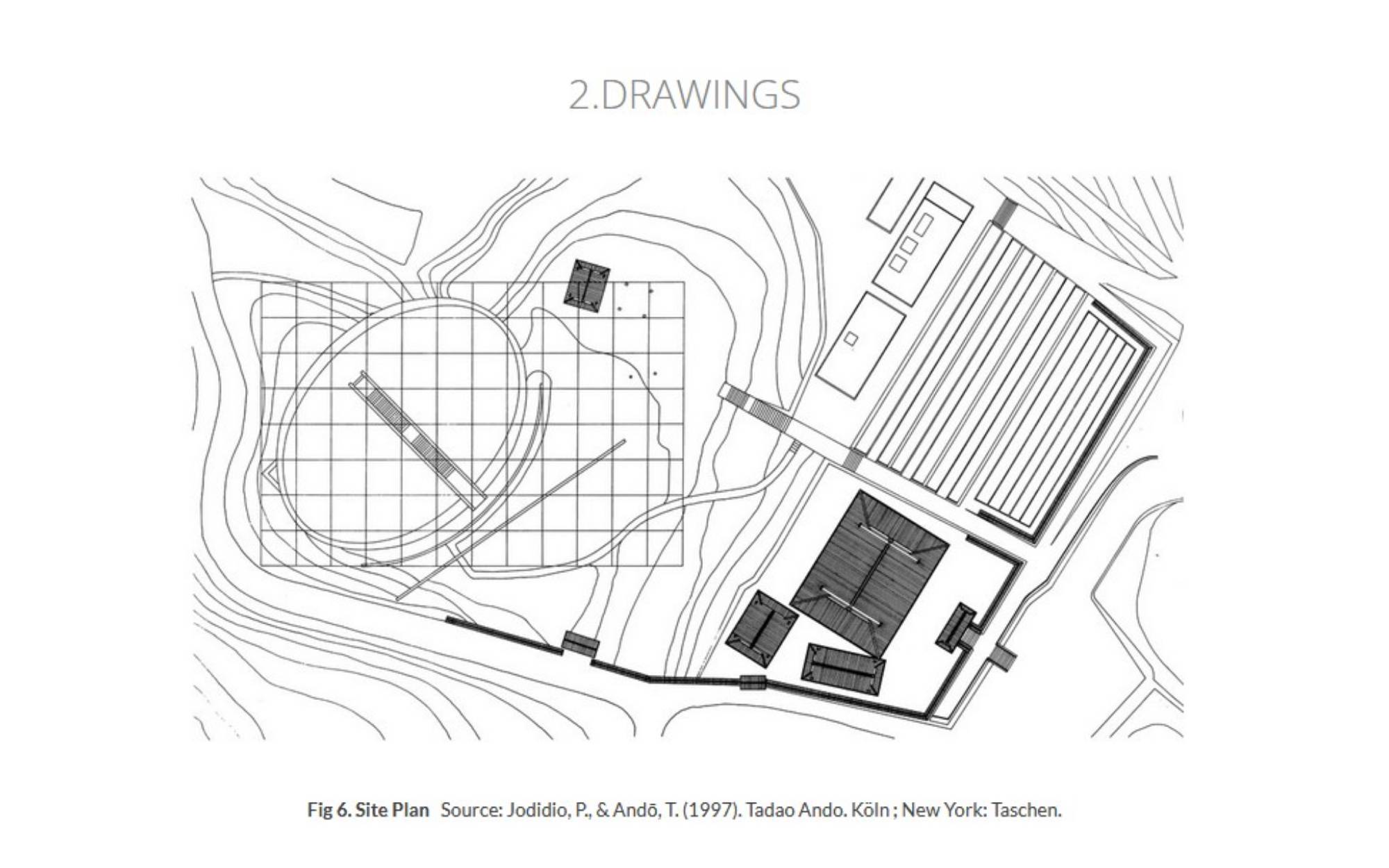

The sequence begins at the older precinct and cemetery, then threads through trees and a curved concrete screen—a threshold separating the everyday from the sacred—before the elliptical pond comes into view. A central stair drops to a circular, vermilion‑washed interior—an unusual, deliberate use of color in Ando’s work—where Yakushi Nyorai is enshrined. At sunset, western light floods in behind the image, a staging that echoes medieval precedents in Hyōgo .

Form, dimensions, and materials

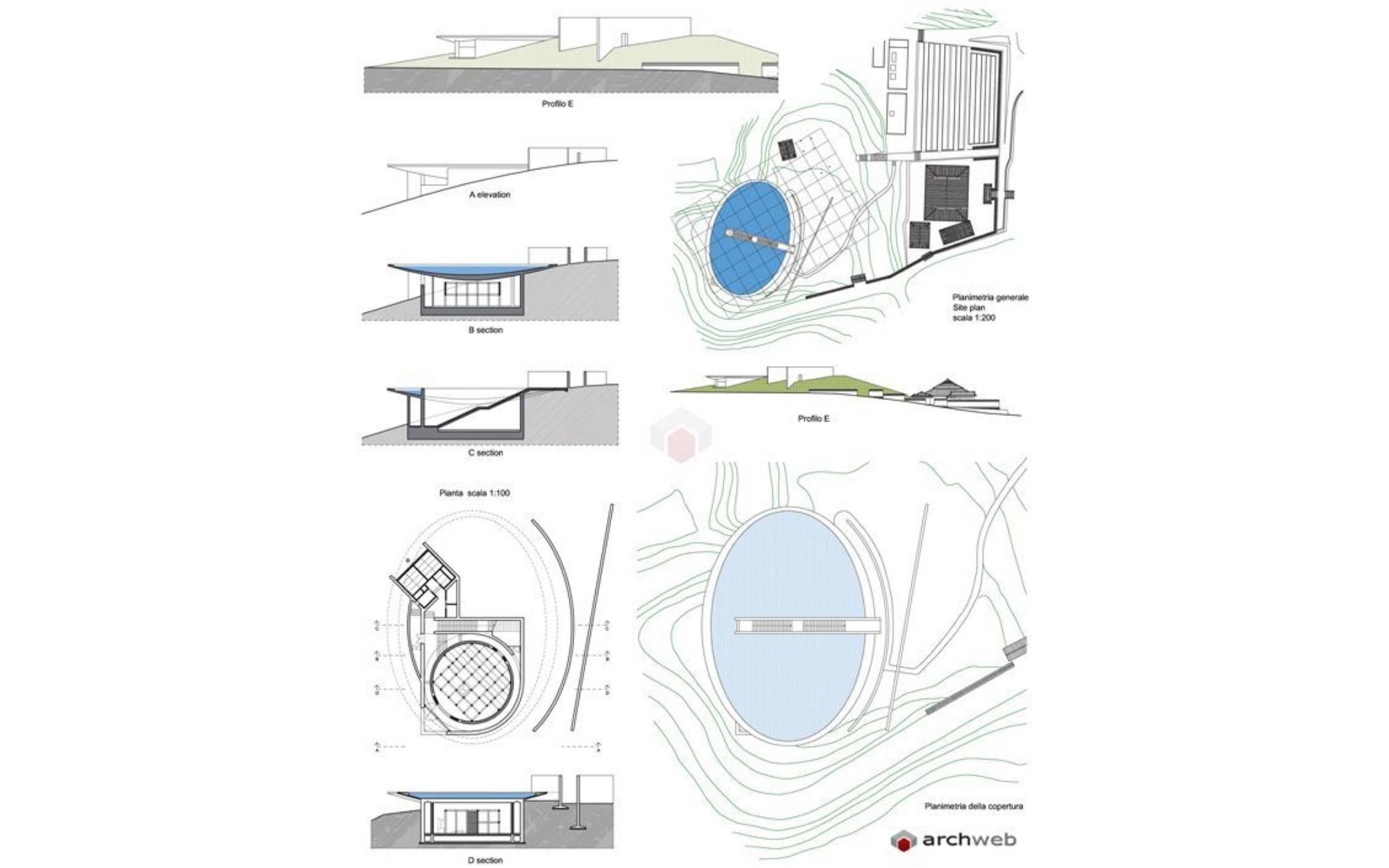

Honpukuji’s water “roof” is a reinforced‑concrete oval pond roughly 40 m by 30 m. The main hall is a one‑story, below‑grade structure in exposed concrete, completed in 1991. The design placed the symbol of awakening (lotus) where the roof would ordinarily announce authority—aligning with Ando’s stated intent to avoid the “power‑symbol” of a big temple roof.

Reception and influence

From the early 1990s the Water Temple was celebrated in Japan and abroad as a radical re‑reading of temple typology—combining procession, abstract geometry, and elemental materials (water, light, concrete) to induce contemplation. It remains a frequently studied work in contemporary architectural history and Ando’s career.

A living temple: seasons and pilgrimage today

Honpukuji is not a museum piece. It remains an active Shingon temple and pilgrimage stop. The lotus pond above the hall carries Ōga lotus (ancient “2000‑year‑old” variety) and waterlilies, blooming from late spring into summer; their growth animates the water plane and sharpens the building’s symbolic reading across the year.

Architecture

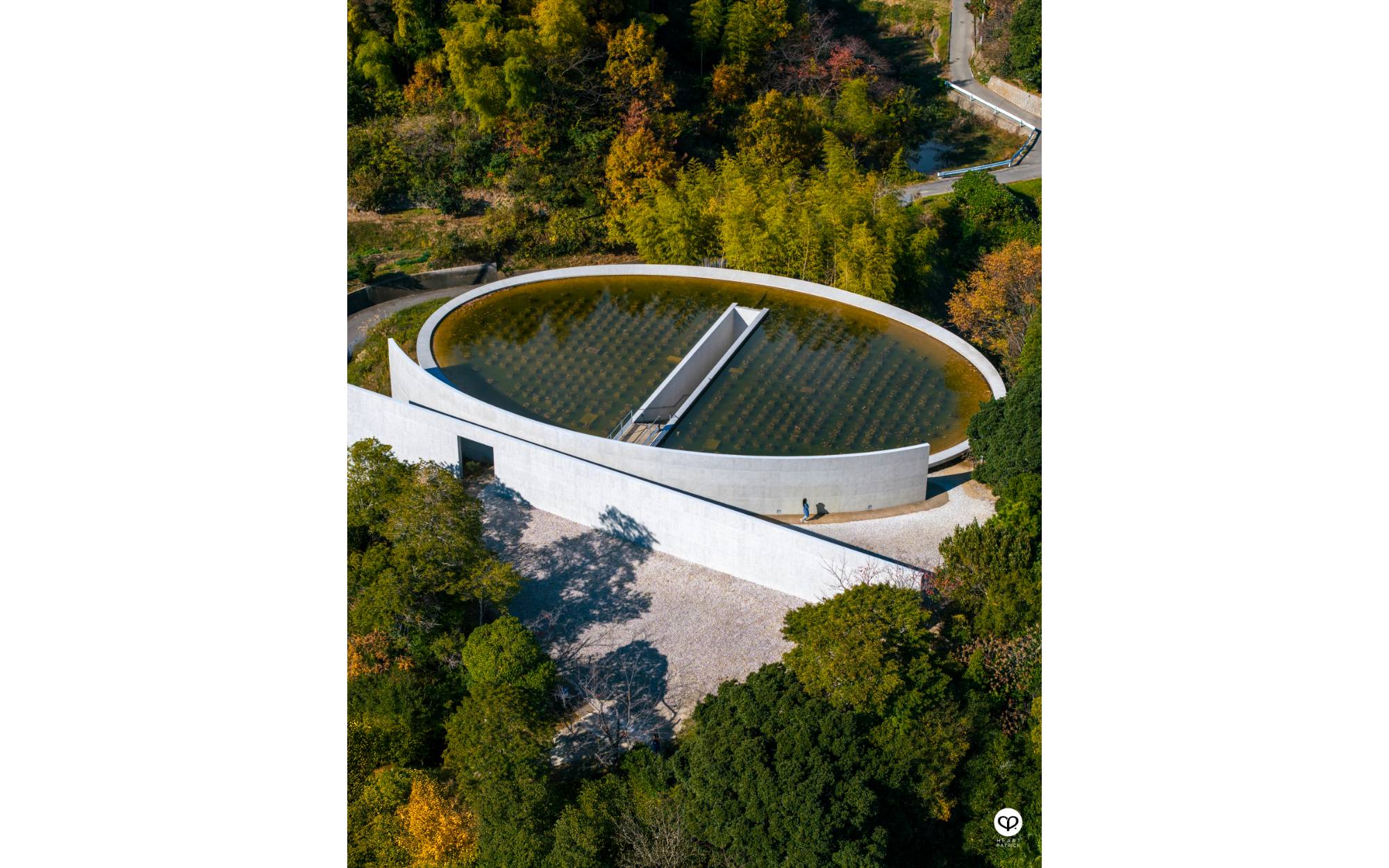

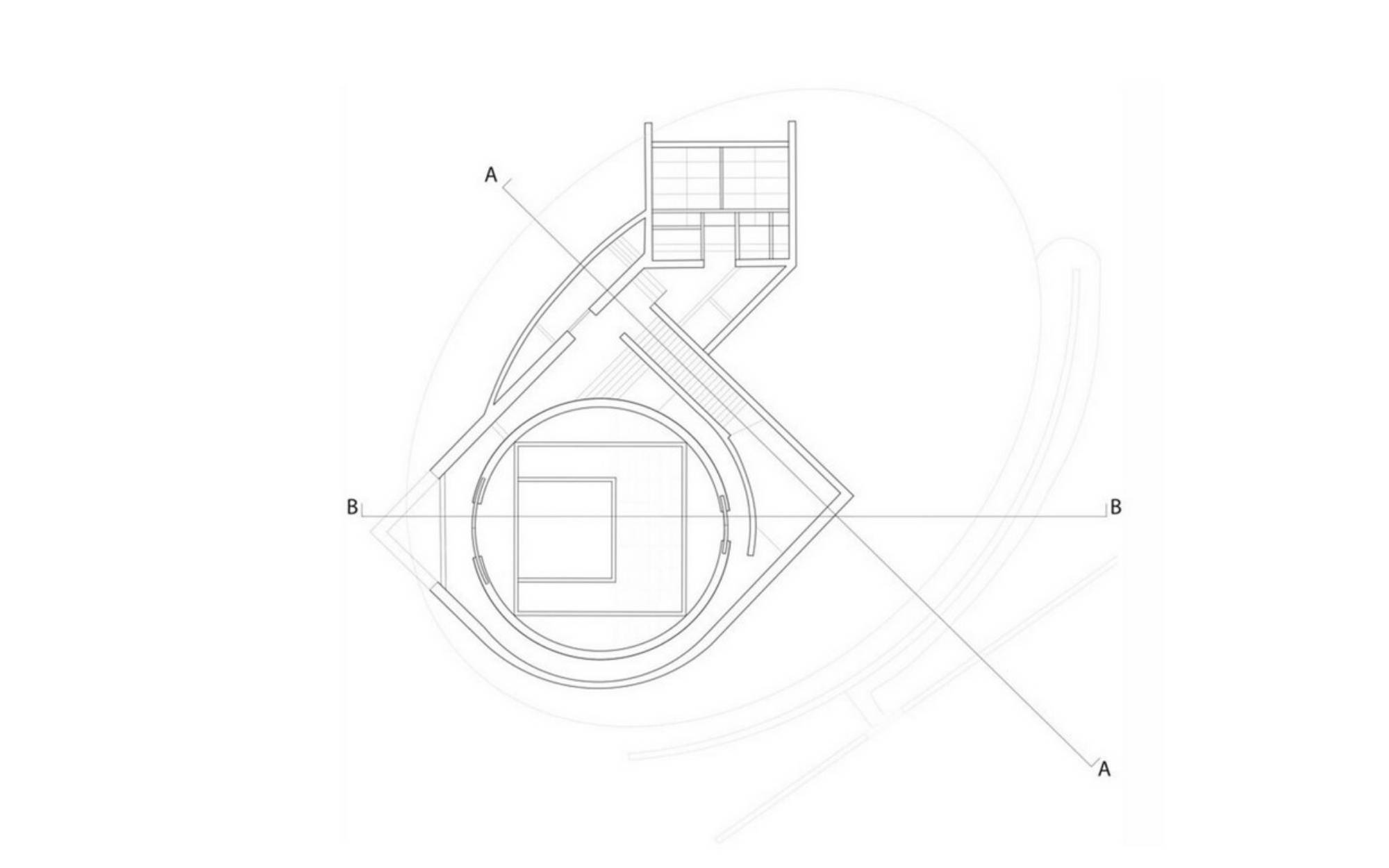

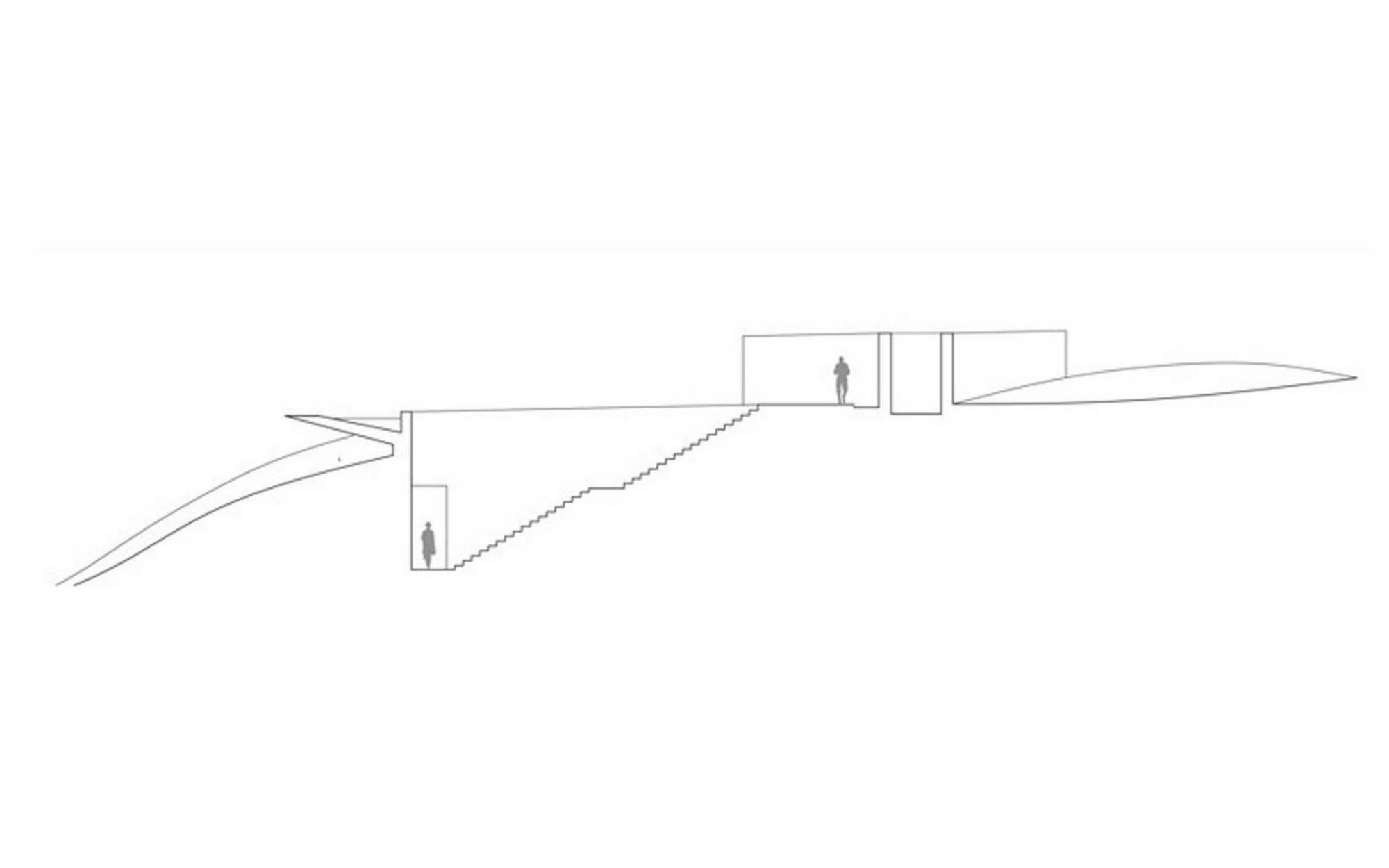

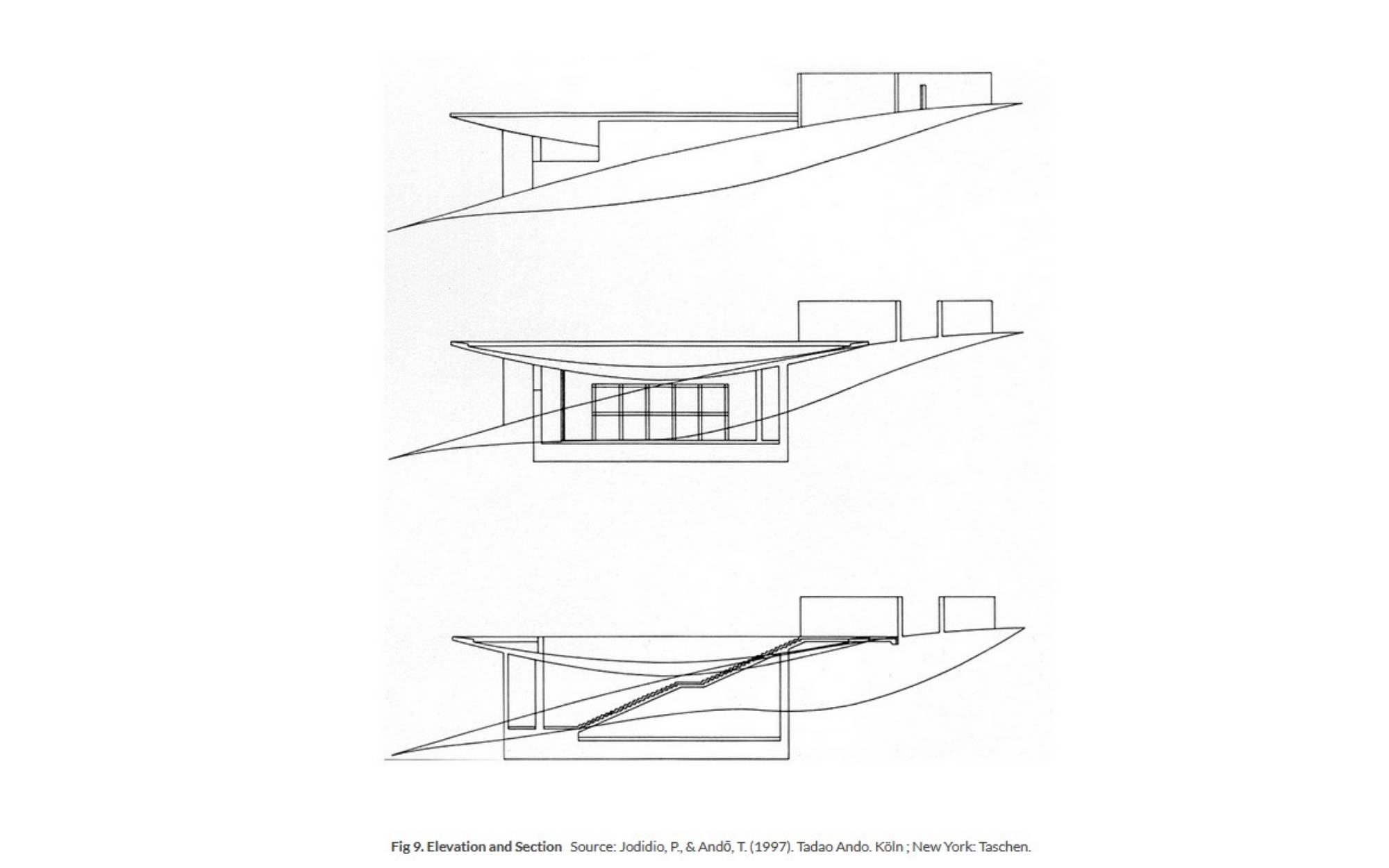

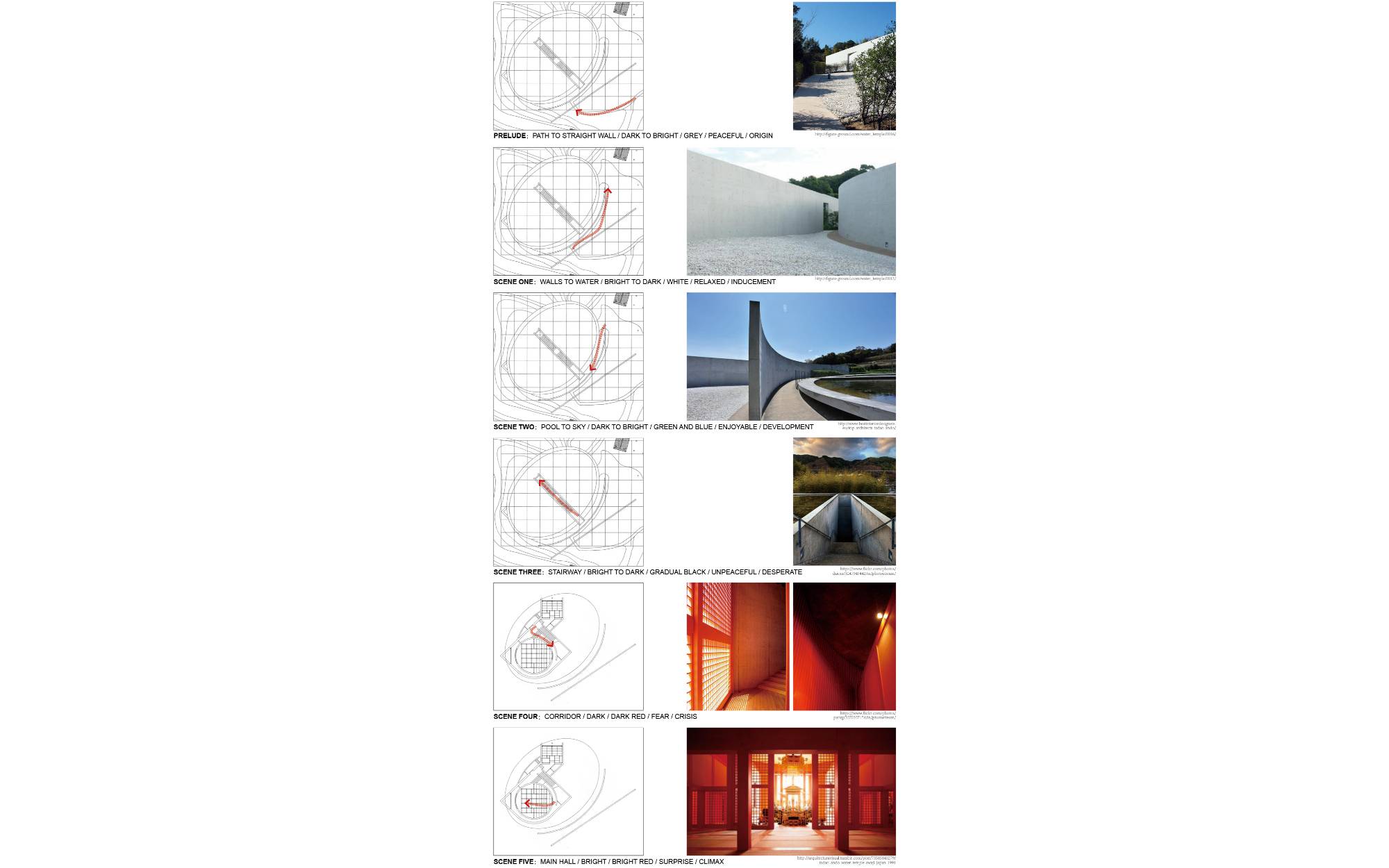

Two polished, 3-meter-tall fair-faced concrete walls guide you along a white-gravel walk toward a broad elliptical lotus pond at the hilltop. A stair slit bisects the water and leads down to the sanctuary below—an inversion of the usual upward ascent to a temple.

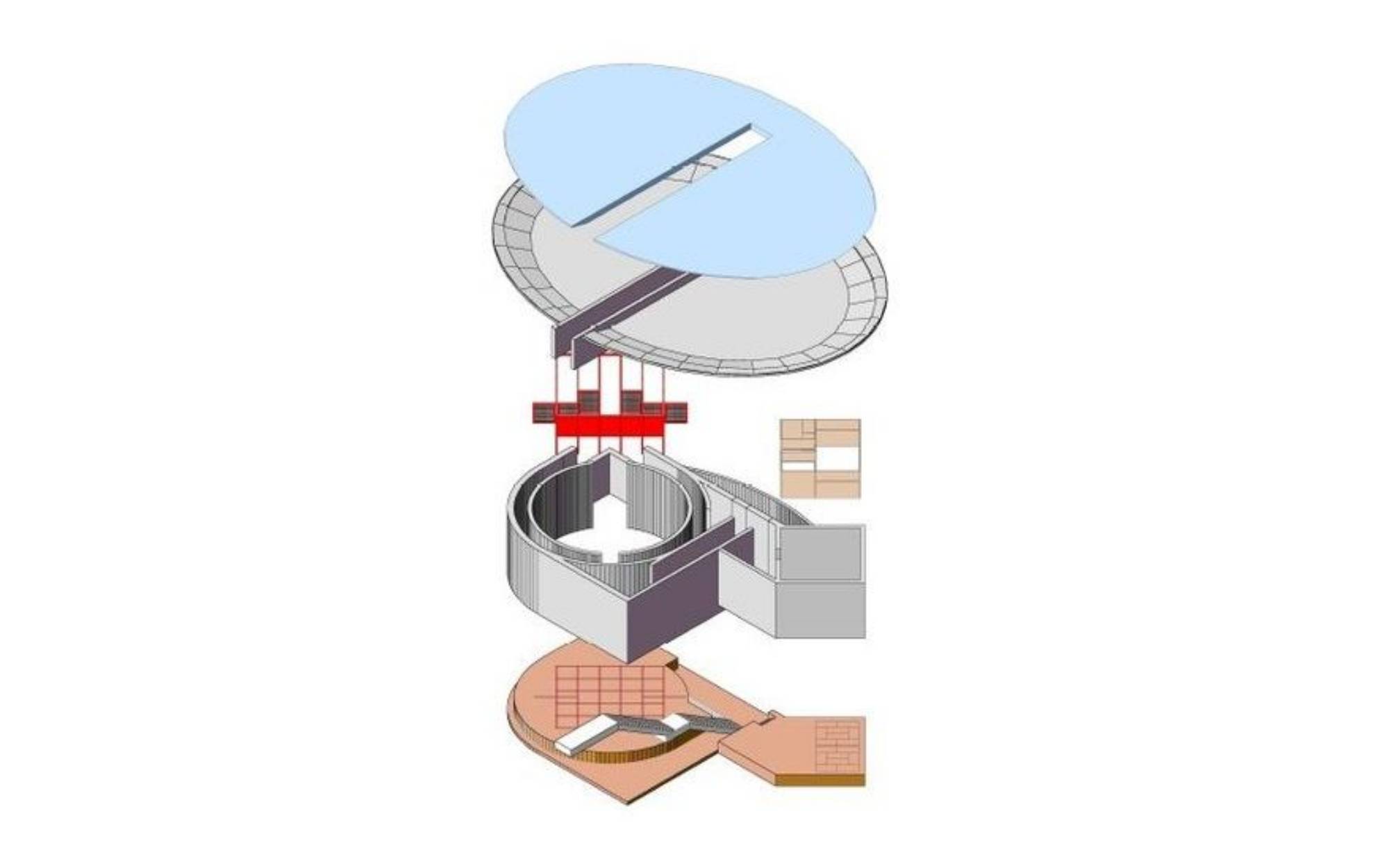

Concept & parti. Tadao Ando replaces the traditional roof with a flat plane of water—a lotus pond that reflects sky and landscape—so the “roof” becomes nature itself. The idea emphasizes elemental forces (earth, light, water) and reframes Pure Land symbolism: the lotus as a sign of rebirth and the passage from profane to sacred as a choreographed descent.

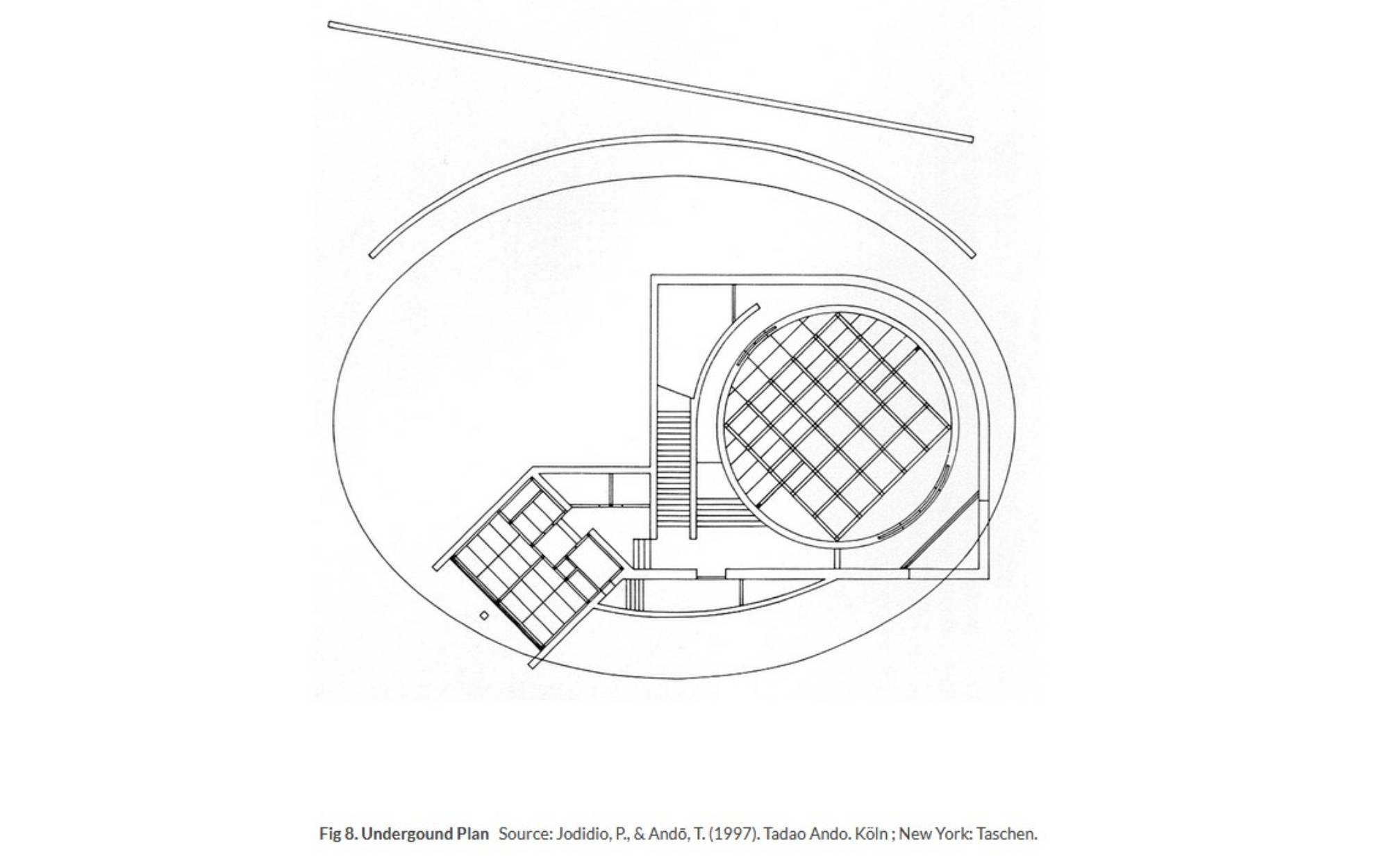

Geometry & plan. The pond’s oval is mirrored below by a simple, concentric composition: a circular worship volume contained within concrete retaining walls. The central stair void splits the plan—one side housing the hall, the other service/ancillary space—so the visitor’s path literally “cuts through” the water to arrive at the sanctuary.

Structure & enclosure. The complex is largely reinforced concrete, expressed as smooth, board-formwork-free planes with regular tie-hole rhythms—a hallmark of Ando’s work. The earth-sheltered hall sits beneath a waterproofed concrete slab that carries the pond; perimeter concrete walls retain soil and brace the bowl-like volume. (Ando’s own descriptions emphasize combining contemporary construction with a modern language while shedding the conventional grand roof.)

Material palette & color. Below the waterline, the sacred room shifts from raw concrete to vermilion-painted timber—gridded lattice screens and posts—over tatami flooring. The intense red field contrasts with the grey envelope and is key to the spatial drama as you move from dim stairs to a glowing inner chamber.

Light & atmosphere. Daylight is filtered through the timber lattice, washing the interior with warm, diffuse light; toward evening, low western sun creates a luminous backdrop behind the altar. The result is a deliberately paced sequence: darkness in the stair trench, soft light in the circular ambulatory, and saturated radiance in the naos.

Water as performer. The pond is not ornamental only; it’s the project’s roof, ceiling, and threshold. It modulates light and reflection above, sets a contemplative soundscape, and frames your arrival with the act of descending “through” the element itself.